Walk 14: The Sloe Road

After a summer none of us will forget, September arrived, ushering in the change in seasons with its mellow sunshine, crisp blue skies and golden light. This has always been my favourite time of year, as the garden gives up the the last of its harvest and the promise of autumn colour and cosy pub fires await.

With only a few walks left for this year, I decided to approach one of the remaining Tonbridge routes that had evaded me so far. Initially I was apprehensive as to how I could spin a story out of a walk with no pub, village or even a church, but I needn’t have worried.

Upon navigating this labyrinth of paths and country lanes I found myself bewitched by the sights and sounds of the hedgerows that lined the route. When I stopped to question these it became clear that not all tales are rooted in bricks and mortar, but sometimes these legends are entwined in the landscape around us.

Time may have moved on and forgotten some of these stories, yet all the time our countryside is protected, there’s every chance later generations will one day find these too.

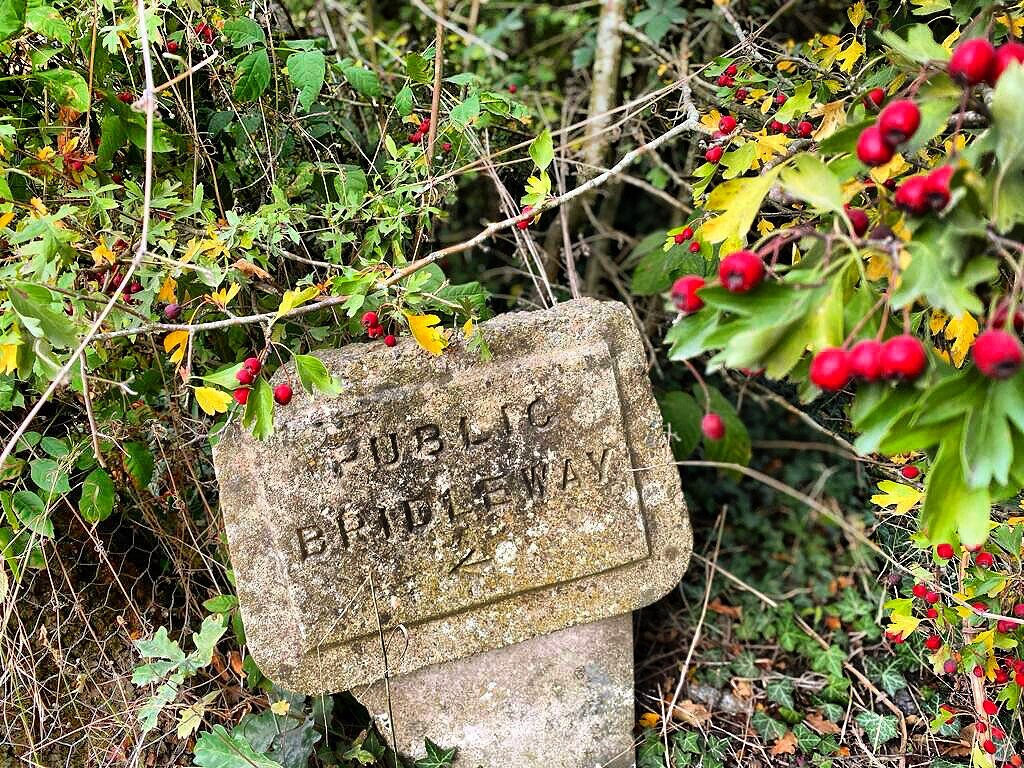

Bridleway marker, Trench Wood

Begin your walk at the very end of Trench Road, near St Margaret Clitheroes school.

Just after the school entrance you will see a bridleway marker and an oil drum at the entrance to the path.

At the beginning…

Follow the pathway through the blackberry bushes until you come to the end of the path. At this point, turn right walking past Little Trench Farm and through the gate, continuing down the wide grass path, flanked either side by tall hedges.

There are an estimated 250,000 miles of managed hedgerow in the UK, providing the stitching in the patchwork of our quintessential British countryside.

Little Trench Farm

At the end of the track continue straight on and you will enter Trench Wood, a thin line of woodland running between the adjacent fields. Tall oak trees wrapped in ivy provide a canopy from the sun and rain. The name Trench derives from the Middle English word Trenche, to mean 'make a cutting through a wood'. The wood here would have been much larger once, before it was cleared to make way for farmland. The slivers of woodland left behind would have originally been used as boundary markers called Shaws. It is these boundaries that formed some of the earliest hedgerows.

Turn left through the kissing gate and then take an immediate right, following another grassy farm track between another pair of large hedgerows. Then at the end of this track turn left again and you will join another wide bridleway, once more bound by tall hedges. The large green gates punctuate the monotony of endless hedgerows and provide a window into the surrounding fields. In Spring these will be filled with fledgling crops, by summer they will be fully grown. Come Autumn you may see stubble or a ploughed field, ready to repeat the life-cycle all over again.

Going through Trench Wood

Most 'modern' hedges date back to the 1700's. Prior to this farming took place in large open fields owned by the local manor. The manorial Lord would divide this 'common land' into strips and lease them to tenants or 'commoners' who could live and farm on these in exchange for a small rent. The worst quality parts of land, for example stony or boggy land, would be leased to the poorest small holders - known then as peasants.

The introduction of the enclosure act entitled the individual portions of land to be sold and consolidated into larger chunks, formalised by the passing of a parliamentary bill. As a result of this, wealthier farmers were able to buy up larger portions of land, increasing their productivity and allowing it to be better farmed. The landlords were also happy because the increased level of production meant they could then maximise the rental value of their estates.

Windows into fields

These packages of land were fenced and hedged, creating new boundaries and pushing many of the peasants and smallholders that once worked and farmed the land into nearby towns and cities in search of work. It is believed that this 'migration' contributed to the subsequent industrial revolution as the thousands of displaced workers took up new jobs in the burgeoning factories.

At the end of the track you will reach Trench Farm, Coldharbour lane. The farm looks incredibly normal with its ramshackle barns and large metal silo tanks, but even the quietest corners of Hildenborough are layered in history. During the second world war these farm buildings were 'home' to some Italian prisoners of war.

Heading for Trench Farm

In the early stages of World War two, prisoners of war (POWs) were a rarity limited to the German airmen that had crash landed or been shot down during bombing raids. This quickly changed following the defeat of Italy during the Western desert campaign in 1941, as the Allied army captured around 130,000 Italian soldiers in Libya and Egypt. Some of these men were shipped to British colonies such as Canada and Australia, but the majority were brought to the UK to stay in POW camps.

Between 1939 and 1948 there were believed to be over 450 camps in Britain - two of which were based in Tonbridge (Somerhill and Mabledon park). Each camp would have had up to 7 satellite hostels, normally based in the surrounding countryside, but prisoners could also be billeted onto local farms such as Trench Farm.

Trench Farm, once home to some Italian prisoners of war

The prisoners played a crucial role in keeping Britain fed, as the country got to grips with the challenges of bringing food safely into its waters. The Nazis had taken occupation of the European channel ports and the Atlantic ocean was filled with U boats. As a result overseas food imports had dropped by 85% since pre-war levels. Britain had increased the amount of crop growing land by a huge 6 million acres but was now relying on this new workforce to farm the extra land.

To begin with, many of the captured men were reluctant to help out, fearing the repercussions of being seen as a traitor on returning to Mussolini's Italy. Those that did work the fields were closely monitored and forced to wear large red circles on their clothing, making them easily identifiable should they try and escape. By the time Italy surrendered in 1943 there were over 100,000 prisoners who were 'co-operators'. No longer seen as a threat these men were afforded a higher wage and were also permitted to mix with local people. They were paid in a camp currency, along with a weekly ration of cigarettes. Non co-operators were restricted to work on the camp itself and received a much lower income.

Trench Farm

Repatriation of the prisoners was a long drawn out process, made slower by the government looking to take advantage of a loophole in the Geneva convention. According to international law, POW status could only be lifted upon the signing of a peace treaty. Although Italy and Germany had surrendered, a peace treaty had not been signed, effectively keeping the POWs in Britain indefinitely. By 1946 there were still over 4000,000 German prisoners living in camps in the UK, maintaining not just farms now, but also assisting with the re-construction of roads and houses.

As the morality of the situation came into question, pressure from both politicians and the public grew, until the government agreed to begin repatriation. In December of that year the German prisoners' restrictions were relaxed and for the first time since the war, they were legally allowed to mix with British people in the local community. That Christmas the POWs were invited into local homes all over the country in a heart warming display of human nature.

Sheep field near Trench Farm

By 1947 an Italian peace treaty had been signed and all of the Italian prisoners had been repatriated. The logistics of returning so many men home, meant that it was to be another year before the German prisoners were repatriated. Given the option to stay on in Britain as civilian workers, around 25,000 men accepted the offer, making the decision to put the war behind them and start a new future in the country that they now called home. You can read more about the role POW's played in agriculture here or for a more personalised account you may wish to read the diary extracts of a German POW that was based in Tonbridge.

Turn right and walk up Coldharbour Lane, then after 200 metres turn left, climbing over the stile and walking through the sheep field. Please remember to keep dogs on a lead when walking through livestock.

Crossing the Hildenbrook

Continue downhill into the corner of the field, then climb the stile and pass over the little wooden bridge as you cross the Hilden Brook. Walk in through the woods, following the path for around 120 metres until you come to a gate on your right. Walk through this and then continue straight on through the fields.

I’ve often seen roe deer darting across this field, heading for Roughetts woods on your right. They are easily startled, so try and spot them before they spot you. Unlike the fallow and sika deer you see at Knole Park, roe deer are native to the UK. Their fur is a rusty red in summer, but appears dark grey/brown in winter.

Across the fields near Roughetts Wood

Continue straight on, passing through two more fields. At the end of the third field, walk through another kissing gate and the path will begin to narrow. The hedges here are crammed with spiky black thorn bushes. In early Autumn these bushes will be brimming with sloe berries. If you negotiate your way past the giant thorns, these sour blue fruits can be plucked from the hedgerow and used in a number of recipes. If you enjoy a tipple then you may want to experiment with a home made sloe gin, or otherwise you could try your hand at making sloe Jam. If you are foraging then remember to follow these basic rules.

At the end of this path you reach a large wooden gate, walk through this and you will emerge onto Riding Lane, at the far fringes of Hildenborough. Turn right and follow the road with care past Hildenbrook Farm. As you pass the entrance to the housing estate, keep an eye out for a tablet dedicated to Ruth Langdon Down - it was her husband Dr Reginald that was one of the original founders of Princess Christian's, a pioneering hospital that once sat here.

Sloe’s growing in the hedgrow

The hospital took its name from Princess Helena, the fifth child of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. Following her marriage to Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein (a Danish born German Prince) the princess followed with tradition and took not only her husband's last name, but also his first name too. In 1895 the princess helped establish the 'National Association for Promoting the Welfare of the Feeble-minded', a trust which intended to provide care and guidance to vulnerable members of society that, if left unaided, would have likely been destined for the lunatic asylum. Victorian Asylums were bleak and often overcrowded, at times blurring the line between prison and hospital. There was no differentiation between mental illnesses and learning disabilities, so often patients would be mixed together and treated the same, regardless of their needs. Society had taken a view that mental illness and disabilities should be out of sight and out of mind with patients hidden away.

With the backing of the trust, the Princess and several Hildenborough residents bought a farm owned by Lord Derby (who I will introduce to you later on in this walk) with the intention of setting up a self supporting farming community that could be run by residents that were affected by severe learning disabilities. The project was chaired by Dr Reginald Langdon Down, whose father John had become the first doctor to classify Down's Syndrome.

Hildenbrook Farm, once the site of Princess Christians Hospital

Princess Christian farm colony opened in 1910 caring for its patients in a quiet rural environment. The male residents would grow vegetables, raise chickens and rear cows. Whereas the ladies would help with cooking and the laundry duties. In those early days the residents would make milk deliveries around the village by a horse driven float. The birth of the NHS in 1948 saw the once private hospital come under ownership of the newly formed National Health Service as Princess Christians Hospital became a subsidiary of the much larger Leybourne Grange hospital.

Despite the takeover the hospital continued for nearly 50 more years, providing a small and caring environment for its 148 residents that lived, worked and played together. The residents lived in a mix of dorms and bungalows and were afforded a great deal of independence, which in turn meant that they could play an active part of the surrounding community. Residents would often be seen around the village at local clubs, or catching a bus into town to do their shopping.

A plaque commemorating Ruth Langdown Down, her husband founded Princess Christians hospital.

Ironically it was the 1990 care in the community act that signified an end to Princess Christians hospital. New legislation triggered the deinstitutionalisation of residential hospitals, encouraging the treatment of patients at home, rather than residential institutions. The hospital closed in 1995 after 85 years of service and was later redeveloped into the housing you see today.

Although the residential aspect of Princess Christians closed, the farm still lives on, albeit in a different capacity and slightly further up Riding Lane. Princess Christian farm is now managed by Hadlow College and provides a special setting for students with learning difficulties or disabilities to develop new skills in an agricultural environment.

Plants for sale at Laundry Cottage

Follow Riding Lane with care for 250 metres passing Laundry Cottage en-route. Depending on the season there is sometimes a selection of beautiful garden plants and tasty homegrown veg for sale. Make sure you keep some cash on you, so you can put payment through the letterbox for any purchases.

Shortly afterwards you will pass the Tardis like ‘Roundhouse’, an unusual shaped house that is much larger than it looks from the front. Just after this house, turn right into the driveway of Fairhill and continue straight on. In Spring the rhododendrons will be in full bloom, showing off their beautiful pink and purple flowers. These attractive shrubs were only introduced to Britain from Europe in 1763, beginning life in the gardens of Stately homes. They have since spread like wildfire, causing mayhem with local ecosystems. Once established they take over the plants around them and then set down roots, safe in the knowledge that their toxic leaves will prevent them from being eaten by native animals and birds.

The rhododendron lined driveway at Fairhill

Pass the gates of Fairhill and then continue along the road uphill. This old mansion house is better hidden than the secrets of its former owners Lord Edward Henry Stanley, the Fifteenth Earl of Derby and his wife Countess Mary. Lord Derby was born into one of the richest families in the UK, owning huge amounts of land in the North of England, including Knowsley Hall near Liverpool. His father was the leader of the conservative party for over 20 years and served as prime Minister three times between 1852-1869. Lord Derby followed in his father's footsteps as a politician and went on to hold various positions in his Dads government.

Prior to her marriage to Lord Derby, Mary had married the 2nd Marquis of Salisbury at the age of 24. Her first husband was 33 years older than her and already spent a similar amount of years in parliament and then later the house of Lords. Mary gave her husband five children, before turning her attention to her political ambitions.

Despite coming from an aristocratic family, the Countess was no stranger to politics. Her father, George Sackville-West, the fifth Earl of De La Warr was a Tory politician and her godfather was no other than the Duke of Wellington (he of the Battle of Waterloo and Napoleon defeating fame), a one time prime minister himself.

Fairhill, Hildenborough, once a home of the Earl of Derby and Countess Mary of Derby

Although women were not allowed to stand for parliament - let alone vote - this did not get in the way of Mary's ambitions to try and shape the political sphere. Drawing on both her aristocratic and political connections she played hostess to influential members of society at the family home, Hatfield House. Up and coming MP's such as Benjamin Disraeli would rub shoulders with journalists and visiting diplomats at afternoon teas and dinner dances organised by the marchioness. Mary would use these opportunities to exchange political news and gossip, as well as attempting to inform, influence and advise her guests on the political issues that concerned her.

After Lord Salisbury died in 1868, Mary re-married to Lord Derby in 1870 and the pair moved to Fairhill. The countess influence grew even stronger when Lord Derby was appointed foreign secretary for a second time, this time serving under the rule of the new Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli. It was during this period that the Countess made her biggest impact on British politics, albeit one that proved costly to both her and her husband.

As Britain teetered on the brink of war with Russia, a power struggle of a different kind was taking place within Britain's own government. The PM was keen to declare war, but Lord Derby, the foreign secretary was not. With friction increasing between the men, the Countess looked to intervene, trading cabinet secrets with a Russian diplomat friend, in hope of keeping the peace.

When rumours of the leaked secrets began to circulate, it quickly became apparent who was to blame. The Countess found herself being severely reprimanded by Queen Victoria who had instructed her chaplain to write to her hinting at the treasonous nature of her actions. The subsequent fall out in the government, and later the press, weakened Lord Derby's standing in the cabinet and destroyed Mary's credibility in political circles, as Fleet Street unfairly hinted that she and the diplomat may have been more than just friends.

The Gates to Fairhill, its secrets are closely guarded compared to its former owners

Lord Derby eventually quit the party a year later, going on to serve with the Liberal Party under Gladstone's government. The Countess supported her husband's move and cut ties with the conservatives, choosing to concentrate her efforts on the liberal government.

The determination and influence that Mary showed in her 'career' makes me wonder just how far the Countess could have pursued her ambitions had she been born in the post suffrage era. Part of me thinks that if she had been around a little later, Britain could have had a female leader much sooner. You can read a more detailed account of these events here.

Twelve Acre plantation, near Fairhill

As you continue along the drive you will see Twelve Acre planation, a large cultivated wood with Christmas trees of all shapes and sizes.

Continue straight on, walking round the metal gate and into Luke’s Wood. The wood itself is private property, so please stick to the path and continue uphill. The climb is noticeable and will be even trickier after wet weather. The wood is pretty though, and the fiery Autumn colours will make up for the lack of a view at the top.

Climbing up through Lukes Wood

Upon leaving the wood, follow the path beside a field of Maize and then climb a stile before crossing a brick bridge over a dry gully. Climb a second stile and then continue along the path between the barbed wire fence and a huge hedge row of hawthorn trees. Hawthorns are the most common type of tree found in the hedgerow and are also one of the oldest native plants in Britain. Their age and prevalence in the countryside has left them steeped in folklore legends.

Sometimes referred to as the Mayflower, these spiky trees transform the hedgrows in Spring when their delicate white flowers burst into life. In pagan times these prized blossoms were used to decorate the May Queen on May Day, traditionally a festival celebrating fertility. Young lovers would sneak off into the woods the night before May Day under the pretence of ‘collecting flowers’, these alfresco liaisons were known as ‘going a Maying’

Young women would wash their faces with the dew drops left on the Hawthorn blossoms in belief that it would make them more beautiful, whilst men would wash their hands in hope that it would make them more skilled craftsmen. Hawthorn branches were never to be bought into the house though, as this was considered to be very unlucky. The smell of the decaying wood was believed to be similar to that of the plague victims and was therefore associated with death and illness.

Hawthorn Hedges

The trees are more than just a pretty flower though. In Spring the new leaves can be eaten raw, despite the nutty taste these were nicknamed bread and cheese in the middle ages, surely one of the earliest examples of a plant based diet?! In Autumn the bushes provide an abundance of glossy red berries called Haws. These are also edible and can be foraged for use in jellies and sauces. I would add that I've not tried these recipes at the time of writing and on a more serious note - never pick berries unless you can be 100% sure what you are picking as some are poisonous.

At the end of this path, climb another stile and continue on as the trail weaves its way under the pine trees. Continue into the open and then follow the path straight on. There will be a cluster of barns and houses on your right.

Haw berries can be used in hedgerow jelly or to make a variant of ketchup

When you reach the road, turn right and follow this past Violets Cottage. If you look up you will see a pair of oast houses, missing their iconic white cowls. Nearly all oasts are converted now, but traditionally the cowl would have acted as chimney, funnelling hot air through the hops drying inside and then out through the roof. The cowl could move with the wind, and would also be waterproof.

Turn left at the ‘Dead slow’ sign and follow the gravel track until you reach a stile. As you climb over you will be able to peek across the top of the hedgerow and enjoy a far reaching view towards Tonbridge.

Looking over the hedge towards Tonbridge

Continue across the paddocks, keeping the hedge on your left and you will see an attractive white house on your right, this is Tinley Lodge farm.

After years of declining numbers (the amount of hedgerows dropped by 50% since the second world war), legal protection was afforded to hedges in 1997, making it a criminal offence to remove a hedgerow aged 30 years or more. The laws were introduced to protect the staggering amount of wildlife that thrive in these semi-natural habitats.

Don't be alarmed if you hear a 'bustle in the hedgerow', according to the RSPB British hedges can support up to 80% of woodland birds, 50% of mammals and 30% of butterflies. The vast amount of insects that make home in the hedges encourages not only birds but also bats, badgers, stoats and of course hedgehogs. The hedgerows provide food, shelter and protection from predators.

Tinley Lodge Farm

As birds nests are also protected by law, the hedges will not be trimmed until the breeding season finishes at the end of August. That's why the hedges may start to look a little straggly come late summer. There are at least 30 species of birds known to nest in hedgerows - with the different types of bird choosing to build their nests at varying heights. For example, Robins and Wrens prefer a spot lower down in the hedge, whereas Turtledoves and Bullfinch normally nest in hedges that are at least 4 metres high. The overgrown grass at the bottom of hedges provides a place for Pheasants to make their nests.

Walk on until you reach another stile and then continue under the mobile phone mast. Keep going along the hedge and as the field dips down towards the woods, climb the stile and continue into Cold Harbour toll. The woods have been heavily forested here, making them bright and airy, as well as leaving plenty of space for the neighbouring sheep to come and explore.

Coldharbour Toll

Coldharbour is a common place name across the UK and it's origins are much debated. The most common theory is that the Cold harbours were old Roman dwellings or settlements that had been left abandoned upon their return. Travellers passing near the old roman roads would use these deserted buildings to lay their head for the night before moving on. As these shelters became well known, entrepreneurs sought to cash in on the passing trade and used the 'harbours' as a place of business, breathing life into the old villages once more. This theory does sound plausible as there is evidence of Roman settlements at Plaxtol and the hill fort at Oldbury, just a few miles North of here.

When you leave the woods, climb another stile and walk uphill through the sheep field. Please keep dogs on a lead at this point.

Walk up the muddy track and into the next sheep field. Across the field to your left you will see Dene Park house on the hill and behind it the huge forest of the same name. If you ever find yourself walking this route at dusk, you are likely to hear the hooting of owls reverberating from the woods.

Stacey’s Wood

Continue across the field, aiming for the gap in the hedge, then climb the stile which will bring you out onto Horns Lodge Lane. Behind the opposite hedge is Cataract Cottage, a lovely old cottage that was commissioned by Countess Derby, when this area was part of the Fairhill estate. If you look over the gate you will see a tiled plaque commemorating a date. This is believed to be the date she underwent a Cataract operation, one of the first in the UK.

Turn right up Horns Lodge Lane, then turn left through the gap in the hedge, continuing across the overgrown meadow using the permissive path. Pass through the metal kissing gate and then follow the path down through the woods of Trench Shaw.

Cataract Cottage, commissioned by Mary Countess Derby

At the end of the path you will reach a T junction where another path crosses. Turn right and you will come to the top of a huge field, occupied by just two trees. After miles of hedgerows and woodland, this vast open space offers up a stunning panoramic view across to South Tonbridge, ending the final part of this walk with a grandstand finish.

Looking across Trench Wood towards Bidborough

Turn left and after a short walk you will come to a kissing gate that leads into Quincewood gardens and leafy North Tonbridge. This marks the end of your walk. If you wish to return to the starting point at Trench Road it will take approximately 8-10 minutes to walk back from here. Alternatively if using public transport it will take a similar amount of time to walk down to the bus stop at Bishops Oak Ride.

Acknowledgements

When I first stumbled across Fairhill everything I researched pointed to Lord Derby. Although he quietly made an impact on the politics of the time, it was his wife Mary which I found more interesting. The nature of my posts mean I have only been able to skim lightly across her story but if like me she has piqued your interest then you may want to consider this book by Jennifer Davey.